It is widely thought that mechanical tuners for stringed instruments started with a linear-pull mechanism, also called a watch-key mechanism, and now most commonly known as Preston tuners.

John Preston claims to have invented these, stamping his with the words “Preston Inventor”. Documentary evidence includes an advert from Hintz in 1766 for an instrument with these tuners, as documented in Holman 2010, together with an English guittar with these from 1767.

The next attribution for mechanical tuning machines goes to Johann Georg Stauffer in Vienna in 1825, who was awarded a patent for “worm-drive” tuners that are the same mechanism as used in modern guitars, mandolins, etc. You can see a modern recreation of Stauffer’s tuning machines here.

Wikipedia (as of today, Nov 10th 2024) backs up this attribution by saying that:

In 1825 Stauffer invented the machine heads named after him: a metal plate with an asymmetrical "scroll" headstock, machine heads with worm gears mounted on the plate, arranged in a single line on the upper side of the head stock (six-in-line).

This is also compounded in the Wikipedia entry on Machine Heads which claims:

Cittern maker John Preston is often credited with a linear-pull tuning machine, appearing in the latter 1700s

Johann Georg Stauffer (1778–1853) was an Austrian luthier generally credited with creating the worm-and-gear tuning machine

It is clearly wrong that Stauffer invented the worm-drive machine head. There are many many examples of instruments from the 1760s onwards that have worm drive machine heads, most likely originating from William Gibson in Dublin.

Well documented and dated examples of instruments bearing these machine heads include:

This English Guitar from 1782 from William Gibson, in the National Music Museum, USA

This English Guitar from 1765 in the V&A London.

This English Guitar from 1772 in Australia.

This English guitar from 1788 restored by Arthur Robb.

The same machine heads also appear on at least ten Sultanas from Thomas Perry, one of Gibson’s fellow Dublin luthiers. These are in collections around the world, such as this example from 1794 and this example dated to the late 1760s.

Some details of Gibson’s life are known: he was the son-in-law of the well-known luthier John Ward and had his premises in College Green (1766-74) and Grafton Street (1768-1790).

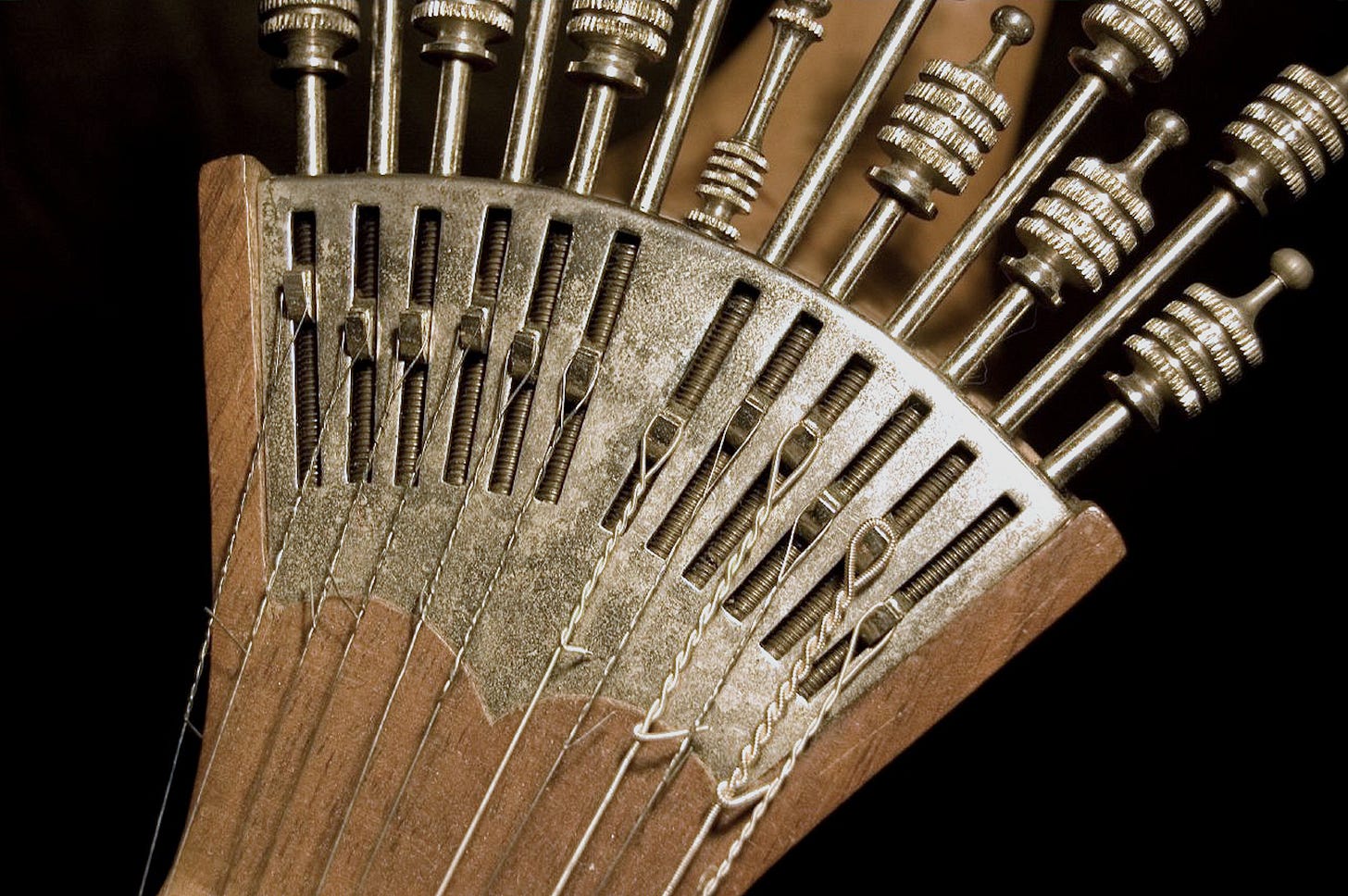

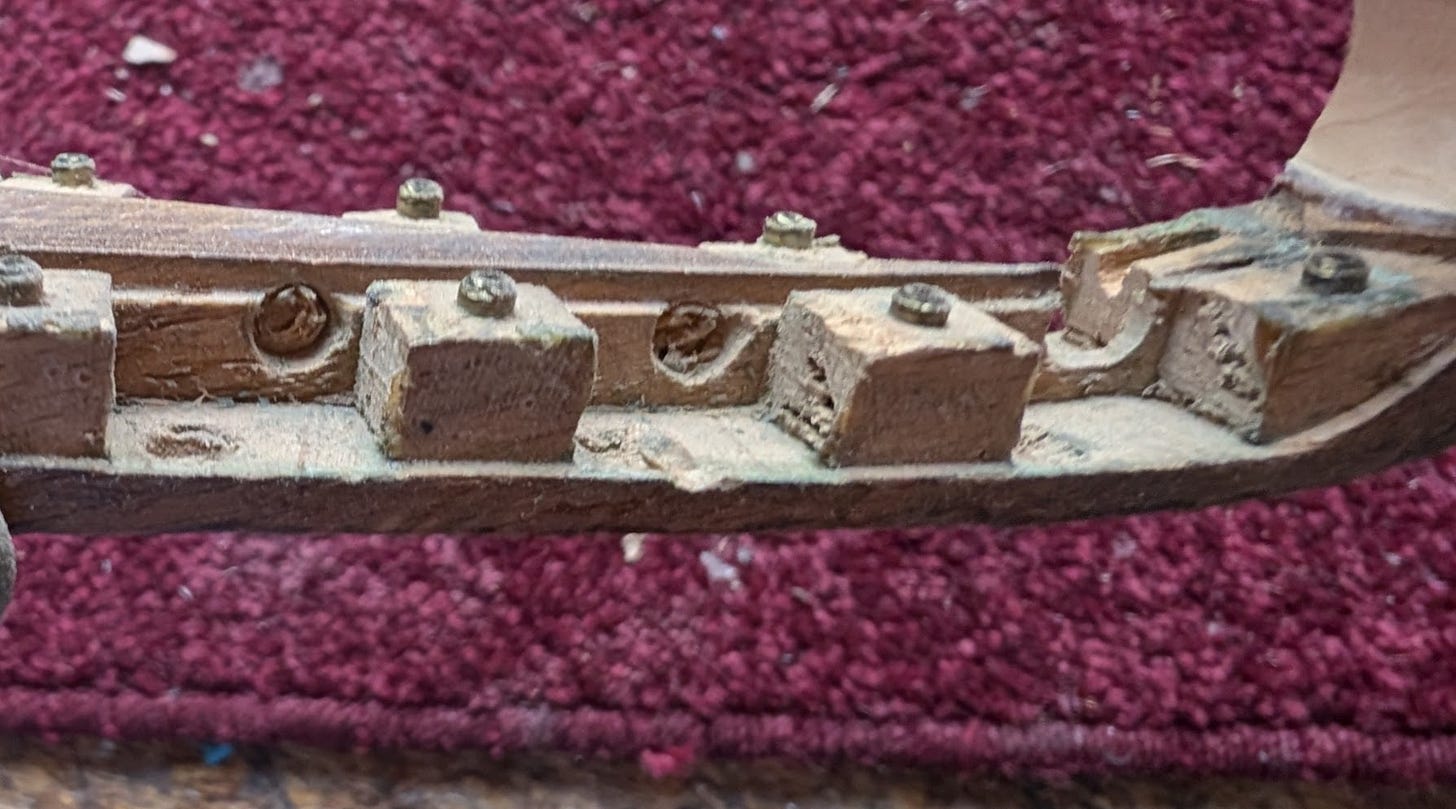

Gibson’s tuning machines consist of a folded and cut brass plate with a delicate cast head in the shape of a ring. Hidden inside the device is a brass worm gear in line with the head and riveted into place between brass walls. This engages with a pinion gear that is connected to the post, which emerges from the top of the brass plate and takes the metal strings used on Guittars and Salters. Each side has 5 tuners and are in mirror image pairs to support 10 strings per instrument.

Alongside the many examples of these tuners, there is documentary evidence: these tuners were discussed in a letter from Charles Clagget to James Watt (yes, that James Watt!) in September 1765, unearthed by Rachael Durkin in her 2023 paper:

“a perpetual screw secreted in the head of ye common form, & the screws are brass and turn a hidden perpetual screw”.

“this is certainly better yn the watch key, but it is more trouble & expense”.

Clagget does not have many good words to say about William Gibson’s reliability, but gives Gibson credit for the tuners, and even includes a sketch of them in his letter.

While this letter implies that the watch key mechanism is already prevalent, this sets the date of the worm-drive tuners at the same time that we first see the watch-key mechanism.

In fact, we can date the Gibson worm-drive tuners to as early as 1764.

I have had the personal experience of examining a 1764 English Guitar in private ownership in Dublin which has these tuners and clearly has had them since it was made.

An even earlier (1763) instrument made by Clagget and Gibson is in the Stearns Collection at the University of Michigan, which also has the 5-on-a-side mechanical worm-drive tuners.

In conclusion, the modern worm-drive mechanical tuner was invented at least 60 years before Stauffer was awarded his patent, and most likely by William Gibson of Dublin. They can be dated to 1763 if not even earlier. It is also possible that the worm-drive was invented before the watch-key mechanism, whose earliest examples also lie in the 1760s. Certainly it was around the same time. The popular credit for the modern machine head still goes to Stauffer despite there being many examples of earlier worm-drive tuners in numerous museums and collections around the world. Let’s hope this misconception can be corrected so that William Gibson of Dublin will justly get the credit for this important invention.

References

Holman, Peter. Life after death: the viola da gamba in Britain from Purcell to Dolmetsch. Vol. 6. Boydell & Brewer, 2010.

Durkin, Rachael. "The Ingenious Mr Charles Clagget: Inventor and ‘Harmonizer’ of Musical Instruments." The Galpin Society journal 77 (2023): 224-247.